Disability Pride Month

July is Disability Pride Month—and at Qi Creative we would like to take a moment to tell you a little more about Disability pride, and what you can do to improve your allyship to disabled friends, family, neighbors, and community members.

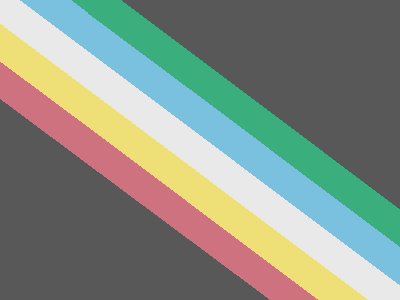

As of October 2021, the Disability Pride Flag has changed to the design below, with straight lines and desaturated colors. Avoid using the older zig-zag flag.

Understandings about disability, in our particular lens as Canadians and as healthcare providers, has shifted greatly over time. What we may have found representative on TV channels, textbooks and lectures, popular culture and media, professional development conferences and disabled speakers and influencers may be long outdated. Disability Pride Month is a great opportunity to refresh your knowledge and expand your perspectives!

While “pride” is often associated with LGBTQIA+ pride, Disability pride is not intended to co-opt the meaning or message of such or other movements. Amber McLinden of Disability Pride Alberta explores this more in depth.

About the Disability Pride Flag

Image description: A charcoal grey flag with a diagonal band from the top left to bottom right corner, made up of five parallel stripes in red, gold, pale grey, blue, and green Description ends

The Disability Pride Flag was a collaborative design effort by Ann Magill, a disabled woman, with feedback within the disabled community to refine its visual elements:

The Black Field: A color of mourning and rage; for those who are victims of Ableist violence, and also rebellion and protest

The Five Colors: The variety of needs and experiences (Invisible and undiagnosed disabilities, physical disabilities, neurodivergence, psychiatric disabilities, sensory disabilities)

The Parallel Stripes: Solidarity within the Disability Community and all its differences

The Diagonal Band: “Cutting across” barriers that separate disabled people; creativity and light cutting through the darkness

Click here to learn how to create the Disability Pride Flag (Ann Magill has waived all copyright claims, and registered the flag under International Public Domain) and on the new resign choices.

Disability Pride Flag Colors

Below are color codes shared by Ann Magill for creating the flag (Hexadecimal and RGB):

Black Field: #585858 (80, 80, 80)

Red Stripe: #CF7280 (207, 114, 123)

Yellow Stripe: #EEDF77 (238, 223, 119)

White Stripe: #E9E9E9 (233, 233, 233)

Blue Stripe: #7AC1E0 (122, 193, 224)

Green Stripe: #3AAF7D (58, 175, 125)

Note that the black color used may seem lighter at first glance than you may be used to using. The Disability Pride Flag image posted above is designed for online screen use, and thus deliberately lightened.

Where Can I Buy a Disability Pride Flag?

The Visually Safe Disability Pride Flag by Ann Magill is marked with CC0 1.0 (Public Domain Declaration). This means that various artists and creators can use the Disability Pride Flag for commercial purposes.

You’re most likely to find the Disability Pride Flag for purchase in various creative marketplaces, such as Etsy and Redbubble.

You may want to try a little extra research to see if the seller is a disabled artist/designer, but again, the design of the flag is open for everyone’s use, commercial or personal.

Avoid Using The Older Flag

The older, ‘lightning bolt’ version of the flag (also called zig-zag flag) causes a strobe/flicker effect when scrolled on electronic devices, and can be a trigger for seizure, migraines, disorientation and other types of eye strain.

The current version is designed to lessen the chances of flicker effects, nausea triggers, and improve visibility for color blindness.

Stick to the redesigned version if you are looking to promote Disability Pride Month, whether it be hanging a Disability Pride Flag in your school or office, or promoting on your websites and social media.

While the ♿️ symbol is easily recognized by both disabled and non-disabled people, a wheelchair only captures one specific dimension of disability—and its medical connotations, as touched upon further below.

What are the Medical and Social Models of Disability?

We can’t mention Disability Pride without also introducing a few topics that influence why the flag was created. There are decades of history and topics within disability rights and disability advocacy that can be touched on, but for this article, we’re beginning with two ‘models’ of disability, what Ableism is, and easy ways to get started with adding disability advocacy to your social feeds.

What are the medical and social models of disability? While the video above is a great intro, what it boils down to is how disability is perceived:

Medical model: My disability prevents meaningful participation. I must act, behave, communicate, or display as close to typical able-bodiedness to participate in my community.

Social model: Society prevents meaningful participation. Through adaptations such as physical modifications in the environment, expanded social policies and cultural inclusion, participation expands to multiple ways of engaging within my community.

Focusing on the medical model—and economic productivity or social performance as markers of ‘success’ or ‘healing’ from disability—creates an emphasis on disability as a lens of deficiency, launching into much of the ableist discourse most disabled people continue to advocate against today (and remains very pervasive—with much research to be done within the intersections of LGBTQIA+, disabled, and people of color)

In present day, while service providers such as ourselves continue to be influenced by medical models, elevating the social model to equal if not stronger importance can help raise equitable participation for everyone—to assist in a therapeutic manner with serious illnesses, disabilities, and other life challenges, while also enhancing community resources, and following our clients’ leads.

What is Ableism?

Image Description: A wide cobblestone roadway. The sides of this roadway are flanked by two sidewalks, one side with only one ramp at the far end of the block, and other continually interrupted by green hedges Description Ends.

Ableism is discrimination against disability.

At its core, Ableism is the assumption that typical abilities are superior to disabilities, and the harmful stereotypes, misconceptions, and generalizations that follow (Access Living, n.d.). It can emerge in different conscious and unconscious forms including (but not limited to):

Environment

Public transportation without adaptations such as ramp entry, or seating for disabled passengers

Able-bodied passengers seated in disabled spaces (e.g. buses, trains), parked in disabled parking spots, using washroom stalls built for disabled people that can fit adaptive equipment

Lack of signage and navigational aids for various physical, cognitive and sensory disabilities

Websites without easy to read fonts and color schemes, described audio, closed captions, or described images, relying only on auto-generated captions versus hiring transcription

Storefronts and curbs without accessible entryways, poorly designed or constructed adaptations

So-called “Ramps” with harsh slants and inclines beyond the accessible usage of wheelchair users

Adaptive public transit services that require significant time in advance to reserve and wait for, or assistance from someone else to reserve

Event venues without quiet rooms/sensory rooms for staff and attendees

Language

Identity-first vs. Person-first usage*

Infantilization; calling a disabled person brave, heroic, or inspiring for their everyday experiences, or conversely, saying you could not live their lifestyle (“you’re amazing, I could never live like you!”)

Correcting a disabled person for their own identity terms and labels

Using language such as "turn a blind eye/tone deaf/that’s lame/crippling/crazy”

Telling someone “but you don’t look disabled” ; relatedly, compliments that frame positivity in spite of disability (eg. “You’re so brave/smart/etc for a disabled person”)

Using a disabled dependent, relative, or friend’s experience to position yourself in disability discourse (eg. “As a parent, I…”)

Asking invasive questions about medical history, especially if you are not in a professional working relationship with a disabled person that requires that information

Obfuscating disabled identification (eg. “Handicapable”, “Differently Abled”, “DisAbility”; “People of Determination”)

Societal Attitudes and Behavior

Skepticism that listening to an audiobook is not reading compared to a physical book

When disability accommodations are considered ‘extra’ or ‘burdensome’, when such accommodations should be the bare minimum for equitable access

Stigmatizing movie tropes about disability (eg. When disabled characters are written-off for various reasons related to rejecting disability; when disabled characters undergo a change or process to become able-bodied—all generally within the ableist lens that the grief, loss, sacrifice, or change was positive)

Movies portraying disabled characters with non-disabled actors; lack of sensitivity readers

Pushing a stranger’s wheelchair as if to support them without asking first; reaching to engage or pet a service dog that is not yours and is trying to support their owner

Perceiving a lack of eye contact as not listening or disrespectful

Perceiving verbal communication as the only form of communication

Pushing to only achieve verbal communication rather than invest in communication that works for the individual (see our blog post AAC Devices and Apps for examples)

Treating deadlines and schedules as sacrosanct, and penalizing those who cannot satisfy artificial time constraints

The rapid adoption of online work and schooling during the COVID-19 onset in 2020, something many disabled people have advocated for—and subsequently, the reduction or cancellation of virtual options when administrations push for in-person or back to office settings

Lack of workplace compliance with disability rights laws

Inspiration Porn (see our blog post)

Not believing in a disability or downplaying the negative outcomes of mishandling one’s health and body, from brain injuries to food allergies

Pushing a disabled person to complete a task or function even as they may openly say they are in pain or distress

* Person-first (“person with autism”) and Identity-first (“autistic person”) are two linguistic descriptions in how we identify people around us. Identity-first is often preferred, in the understanding that Person-first language continues stigma around disabilities. Ultimately, it is best to follow how a disabled person would like to address themselves.

[Ableism is] a system that places value on people’s bodies and minds based on societally constructed ideas of normalcy, intelligence, and excellence.

Talila A. Lewis, Disability Advocate

Support Disabled Creators

If you consider yourself somewhat of a newbie learning about disability and inclusion, one of the easiest ways to add disabled voices to your spaces are by opening yourself to their channels of communication. Listen, learn, and go from there.

Follow disabled creators on social media. Subscribe to their newsletters and channels. Buy products and books from their stores. Donate to their causes. Give disabled voices platforms and pay for their expertise.

There are many disabled leaders, creators, influencers, collectives, charities, support groups, communities and more that are doing work year-round. Rather than trying to strike some new approach or fundraiser just for Disability Pride Month, look to where disabled people have already been doing the work—and support them.

Here is a short, non-exhaustive list to get started:

Dr. Jaipreet Virdi - Disability historian

Alice Wong - Creator and amplifier of disability media & culture; the Disability Visibility Project

Liam O’Dell - Journalist, theatre critic and campaigner (#CCMeIn raising awareness of deaf & hard of hearing people)

The Disabled List - Disability-led, self advocacy organization curating disabled creators and partnerships

Melissa Blake - Blogger, selfie taker, empowering others with #DisabledJoy

Haben Girma - Deafblind advocate, lawyer, writer, speaker & accessible technology expert

Carly Findlay - Disability rights campaigner and author of Say Hello - Things they don’t tell you about being a Disability Activist

Amit Patel - Author of Kika and Me

Disability History In Canada: Present Work In The Field And Future Prospects by Geoffrey Reaume, PhD

Hannah Barnham-Brown - Doctor, politician, speaker, #RollModel and disability advocate

And see our previous Black Lives Matter post for a non-exhaustive list of Black and Disabled influencers.

And from our Qi Creative blog archives:

Disability Pride Reading Lists

Inclusivity, accuracy, and disabled authorship in books and media depictions is rising. Looking to fill your days under the sun with a book? Check out these book lists, blogs, and articles:

If your disability inclusion doesn’t include intersectionality, it isn’t inclusion.

We mentioned earlier that Disability Pride does not exist to take or appropriate from other important movements; however, it’s important to include the diverse backgrounds and lived experiences in your advocacy.

Some hashtags to explore on your social media may include the following below. These links redirect to Twitter/X (as this blog was originally published in 2020), but hashtags can be incorporated among multiple platforms:

Hashtags are more than just trending words—they have legitimate utility as organization tools among disabled communities.

Related Links:

What we can learn from the Disabled community during COVID-19

Crip Camp - A Netflix original documentary film

IN A BEAT - Original short film by 37 LAINES

Can I Play That - Game writing publication by disabled gamers, exploring accessibility in games for deaf and hard of hearing; motor/physical accessibility; cognitive accessibility; blind and low-vision; and colourblindness.

Believe, Listen, and Learn

While we’ve mentioned current and historical topics shaping Disability Pride movements, it is important to continue to educate yourself, and continue to listen and learn from those around you.

Believe people, unconditionally, when they disclose a disability — don’t accuse people of ‘faking’ their disabilities, their adaptations, their boundaries and their needs.

Planning an event? Be more conscientious about the venue’s accessibility. A single elevator on the other side of the auditorium is not accessible. Consider lighting and glare, navigation, ambient sound, and access to a multipurpose quiet room. Take accommodation requests seriously.

Talk about disability with your children, and do so with a neutral stance (eg. They are a wheelchair user; not, ‘something awful must have happened’).

Keep invasive questions about disabilities to yourself, especially if you do not know them well.

Tread lightly and respectfully - Disability Pride Month can be an exhausting period for disabled people, whether or not they speak or advocate publicly.

Explore the policies and practices of your workplaces, the accessibility of your physical location; and with considerations of ableism mentioned earlier in this blog, advocate for change.

Believe, listen, and learn.

“Someone with a diagnosis of ‘mild autism’ doesn’t mean that they experience their autism mildly; it means that *YOU* experience their autism mildly.”